LOCATION: İzmir / Turkey

CLIENT: Architecture For Humanity

CATEGORY: Competition / Urban Design / Public Space / Waterfront / Conservation / Building / Culture / Industrial Heritage

STATUS: International Competition (Semi-Finalist)

AREA (OUTDOORS): 153.460 sqm

TIMETABLE:

Competition: June 2012

DESIGN OFFICE/S

Studio Evren Başbuğ Architects

CREDITS:

Architectural Concept:

Evren Başbuğ (Lead Architect / Studio Evren Başbuğ Architects)

Architectural Design Group:

Evren Başbuğ (Lead Architect / Studio Evren Başbuğ Architects)

Umut Başbuğ (Architect / Studio Evren Başbuğ Architects)

Hüseyin Komşuoğlu (Architect / Studio Evren Başbuğ Architects) Can Kaya (Architect) Tuba Çakıroğlu Özerim (Architect) Erdem Yıldırım (Architect) Ebru Bingöl (Landscape Architect) Can Karyaldız (Architect / TH&İDİL Architects) Sinan Demirel (Undergraduate Student)

Consultants:

Assoc. Prof. Güven İncirlioğlu (Architect, Artist)

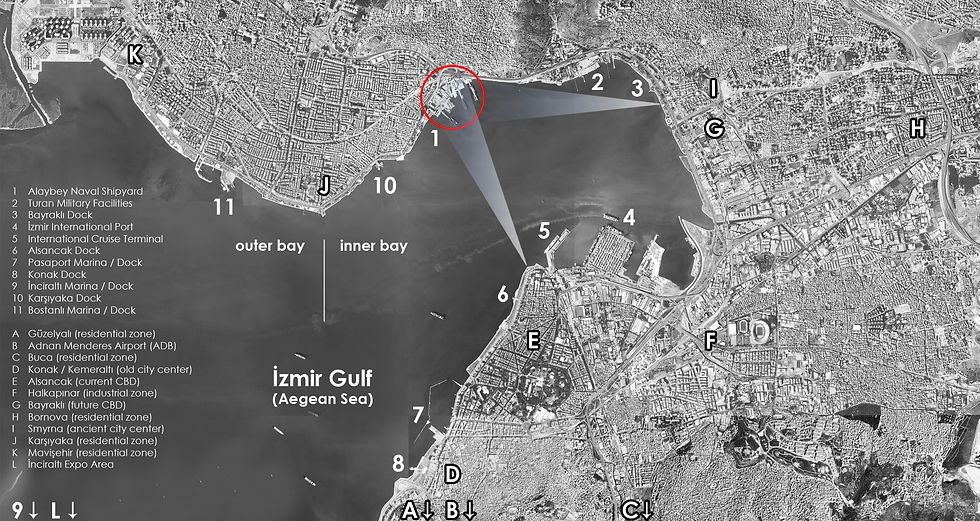

Having been used as the main construction and maintenance facility of the navy for almost over 50 years, 'Alaybey Naval Shipyard' in İzmir, Turkey is soon to be moved. Settled on one of the most valuable fragments of the urban coastline, the facility covers a surface area of nearly 135.000 sq. meters. It has been performing its heavy industrial duties in the heart of the city with a standard military level of clearance; the complex is surrounded by walls and protected by armed guards. All kinds of gunboats and battleships sail in and out of the wavy blue waters of the gulf regularly; posing a grey, metallic scenery for the city. Easily seen from most of the surrounding coastline throughout the city, the facility itself also stands as a focal point with its distinctively huge, steel cranes and other industrial structures.

A large number of military installations in Turkey’s biggest cities are already in the most congested urban areas. The populations of İstanbul, Ankara and İzmir are almost tenfold compared to mid twentieth century, when these military installations were constructed. On one hand, these islands within the (inner) cities are considered to be breathing spaces, with scattered low buildings and many trees, much like some defunct industrial complexes within the central urban areas, like the coal-gas plants. Meanwhile, the tendency of central and local governments is to turn these valuable urban-public properties into money-making enterprises, by renting them out for periods of 25 or 49 years, and allowing the zoning for high-rise residences and shopping malls.

Among the examples are old cigarette and liquor factories that belonged to the Turkish state monopolies, old port areas in İstanbul, some old school buildings and the like. Interestingly, this neo-liberal scheme in Turkey will soon privatize (and sell) main train station in İstanbul, the surrounding container port, the old tobacco warehouses in İzmir, and some facilities of the state railroads in Ankara and elsewhere. The case of the urban military zones within this outlook is a little more complex. For the military headquarters, command centers and the surrounding housing for military personnel, evacuation is mostly out of question. For less important military sites (like barracks and depots and the like) a deal is usually worked out with the central government so that they can be transferred outside city limits and be re-located. Among these strategically less important military facilities are the naval shipyards (now almost out of use, except for minor repairs) on the Golden Horn in İstanbul. Negotiations are under way for the fate of these waterfront properties, to turn them into cultural centers, museums of industry, recreational areas, and indeed to introduce some profitable commercial activities. Apparently, a mixture of culture and commerce is seen as a convenient way of privatizing and gentrifying public property.

Even though İzmir, throughout history, enjoyed a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural social life and a relatively wealthy mercantile class, in the past century or so it had been more monochrome and a little bit provincial, partially losing its chances to become a major actor among the port cities of the Mediterranean and global cities of the world. İzmir’s recuperation is slow with limited investment from the outside world, albeit with a growing population now around three and a half million. So, in İzmir similar ventures of urban renewal and regeneration mostly appear to be not so feasible in financial terms as the cultural and commercial activity in the city and its hinterland is for now limited. As an example, the existing container port in İzmir and its surroundings have for quite some time been considered for alternative uses, albeit for now without the needed funds.

In a similar vein, in the long run one may expect Alaybey Shipyard to be moved outside the Gulf of İzmir since it has a tense relationship with its surroundings like any other military zone squeezed in the urban setting;

By its location, the shipyard harms the continuity of the coastline both physically and visually.

By its impermeable walls, the shipyard segregates the urban space into two distinct zones.

By its paranoid mindset, the shipyard creates a sensory tension with its surroundings.

On the contrary, for now, we propose that it keeps working in a modified way, instead of proposing a future scenario in which it is decommissioned. The reasons for this choice are manifold. If the facility is moved to elsewhere, we believe that we would end up with an un-coded huge empty space torn apart from its collective memory. And with all the industrial structures gone, the city would lose one of its scenic urban elements; not to mention the social and economic dynamics to be shattered. We would not want to impose a new function for this urban waterfront property in the name of public good. Our aim is, in one sense, to reconcile an (old) production method and craft (shipbuilding), and the lay person at large. Indeed, this encounter also brings together the military personnel and the civilian population, or in other words, it aims to infuse civic life into a militarized zone. Our aim is not to create a theme park out of a military-industrial activity, but to allow a sort of interaction.

In this manner the existing protective wall of the complex is penetrated numerous times both visually and physically. Some fragments of the wall are turned into semi-transparent surfaces allowing a visual interaction with the activities and the personnel inside. A high public terrace over the existing wall makes possible a kind of 'inverted' gaze in which the public surveys the military zone and the industrial activity. The waterfront pedestrian strip along the gulf of İzmir is allowed to continue and wrap around the shipyard, enabling a permeating zone complemented by a hybrid space carved out of the complex, hosting the educational facilities. Equipped with a series of outdoor venues (regularly hosting movie screenings throughout the year) the continuous pedestrian zone ironically turns the shipyard into the object of 'gaze'. This provocative approach generates an awkward situation of which we define as the 'reciprocal gaze'.

Comentários